O VERVIEW

Since immigration statistics usually combine information about New Zealand with that of Australia, and because similarities between the countries are great, they are linked in this essay also. The Commonwealth of Australia, the world's sixth largest nation, lies between the South Pacific and the Indian Ocean. Australia is the only country in the world that is also a continent, and the only continent that lies entirely within the Southern Hemisphere. The name Australia comes from the Latin word australis , which means southern. Australia is popularly referred to as "Down Under"—an expression that derives from the country's location below the equator. Off the southeast coast lies the island state of Tasmania; together they form the Commonwealth of Australia. The capital city is Canberra.

Australia covers an area of 2,966,150 square miles—almost as large as the continental United States, excluding Alaska. Unlike the United States, Australia's population in 1994 was only 17,800,000; the country is sparsely settled, with an average of just six persons per square mile of territory as compared to more than 70 in the United States. This statistic is somewhat misleading, though, because the vast Australian interior—known as the "Outback"—is mostly flat desert or arid grassland with few settlements. A person standing on Ayers Rock, in the middle of the continent, would have to travel at least 1,000 miles in any direction to reach the sea. Australia is very dry. In some parts of the country rain may not fall for years at a time and no rivers run. As a result, most of the country's 17.53 million inhabitants live in a narrow strip along the coast, where there is adequate rainfall. The southeastern coastal region is home to the bulk of this population. Two major cities located there are Sydney, the nation's largest city with more than 3.6 million residents, and Melbourne with 3.1 million. Both cities, like the rest of Australia, have undergone profound demographic change in recent years.

New Zealand, located about 1,200 miles to the southeast of Australia, comprises two main islands, North Island and South Island, the self-governing Cook Island and several dependencies, in addition to several small outlying islands, including Stewart Island, the Chatham Islands, Auckland Islands, Kermadec Islands, Campbell Island, the Antipodes, Three Kings Island, Bounty Island, Snares Island, and Solander Island. New Zealand's population was estimated at 3,524,800 in 1994. Excluding its dependencies, the country occupies an area of 103,884 square miles, about the size of Colorado, and has a population density of 33.9 persons per square mile. New Zealand's geographical features vary from the Southern Alps and fjords on South Island to the volcanoes, hot springs, and geysers on North Island. Because the outlying islands are scattered widely, they vary in climate from tropical to the antarctic.

The immigrant population of Australia and New Zealand is predominantly English, Irish, and Scottish in background. According to the 1947 Australian census, more than 90 percent of the population, excluding the Aboriginal native people, was native-born. That was the highest level since the beginning of European settlement 159 earlier, at which time almost 98 percent of the population had been born in Australia, the United Kingdom, Ireland, or New Zealand. Australia's annual birth rate stands at just 15 per 1,000 of population, New Zealand at 17 per 1,000. These low numbers, quite similar to U.S. rates, have contributed only nominally to their population, which has jumped by about three million since 1980. Most of this increase has come about because of changes in immigration policies. Restrictions based on a would-be immigrant's country of origin and color were ended in Australia in 1973 and the government initiated plans to attract non-British groups as well as refugees. As a result, Australia's ethnic and linguistic mix has become relatively diversified over the last two decades. This has had an impact on virtually every aspect of Australian life and culture. According to the latest census data, the Australian and British-born population has dropped to about 84 percent. Far more people apply to enter Australia each year than are accepted as immigrants.

Australia enjoys one of the world's highest standards of living; its per capita income of more than $16,700 (U.S.) is among the world's highest. New Zealand's per capita income is $12,600, compared with the United States at $21,800, Canada at $19,500, India at $350, and Vietnam at $230. Similarly, the average life expectancy at birth, 73 for an Australian male and 80 for a female, are comparable to the U.S. figures of 72 and 79, respectively.

HISTORY

Australia's first inhabitants were dark-skinned nomadic hunters who arrived around 35,000 B.C. Anthropologists believe these Aborigines came from Southeast Asia by crossing a land bridge that existed at the time. Their Stone Age culture remained largely unchanged for thousands of generations, until the coming of European explorers and traders. There is some evidence that Chinese mariners visited the north coast of Australia, near the present site of the city of Darwin as early as the fourteenth century. However, their impact was minimal. European exploration began in 1606, when a Dutch explorer named Willem Jansz sailed into the Gulf of Carpentaria. During the next 30 years, Dutch navigators charted much of the northern and western coastline of what they called New Holland. The Dutch did not colonize Australia, thus in 1770 when the British explorer Captain James Cook landed at Botany Bay, near the site of the present city of Sydney, he claimed the whole of the east coast of Australia for Britain, naming it New South Wales. In 1642, the Dutch navigator, A. J. Tasman, reached New Zealand where Polynesian Maoris were inhabitants. Between 1769 and 1777, Captain James Cook visited the island four times, making several unsuccessful attempts at colonization. Interestingly, among Cook's crew were several Americans from the 13 colonies, and the American connection with Australia did not end there.

It was the 1776 American Revolution half a world away that proved to be the impetus for large-scale British colonization of Australia. The government in London had been "transporting" petty criminals from its overcrowded jails to the North American colonies. When the American colonies seized their independence, it became necessary to find an alternate destination for this human cargo. Botany Bay seemed the ideal site: it was 14,000 miles from England, uncolonized by other European powers, enjoyed a favorable climate, and it was strategically located to help provide security for Great Britain's long-distance shipping lines to economically vital interests in India.

"English lawmakers wished not only to get rid of the 'criminal class' but if possible to forget about it," wrote the late Robert Hughes, an Australian-born art critic for Time magazine, in his popular 1987 book, The Fatal Shore: A History of Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787-1868 . To further both of these aims, in 1787 the British government dispatched a fleet of 11 ships under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip to establish a penal colony at Botany Bay. Phillip landed January 26, 1788, with about 1,000 settlers, more than half of whom were convicts; males outnumbered females nearly three to one. Over the 80 years until the practice officially ended in 1868, England transported more than 160,000 men, women, and children to Australia. In Hughes' words, this was the "largest forced exile of citizens at the behest of a European government in pre-modern history."

In the beginning, most of the people exiled to Australia from Great Britain were conspicuously unfit for survival in their new home. To the Aborigines who encountered these strange white people, it must have seemed that they lived on the edge of starvation in the midst of plenty. The relationship between the colonists and the estimated 300,000 indigenous people who are thought to have inhabited Australia in the 1780s was marked by mutual misunderstanding at the best of times, and outright hostility the rest of the time. It was mainly because of the vastness of the arid Outback that Australia's Aboriginal people were able to find refuge from the bloody "pacification by force," which was practiced by many whites in the mid-nineteenth century.

Australia's population today includes about 210,000 Aboriginal people, many of whom are of mixed white ancestry; approximately a quarter of a million Maori descendants currently reside in New Zealand. In 1840, the New Zealand Company established the first permanent settlement there. A treaty granted the Maoris possession of their land in exchange for their recognition of the sovereignty of the British crown; it was made a separate colony the following year and was granted self-governance ten years later. This did not stop white settlers from battling the Maoris over land.

Aborigines survived for thousands of years by living a simple, nomadic lifestyle. Not surprisingly the conflict between traditional Aboriginal values and those of the predominant white, urbanized, industrialized majority has been disastrous. In the 1920s and early 1930s, recognizing the need to protect what remained of the native population, the Australian government established a series of Aboriginal land reserves. Well-intentioned though the plan may have been, critics now charge that the net effect of establishing reservations has been to segregate and "ghettoize" Aboriginal people rather than to preserve their traditional culture and way of life. Statistics seem to bear this out, for Australia's native population has shrunk to about 50,000 full-blooded Aborigines and about 160,000 with mixed blood.

Many Aborigines today live in traditional communities on the reservations that have been set up in rural areas of the country, but a growing number of young people have moved into the cities. The results have been traumatic: poverty, cultural dislocation, dispossession, and disease have taken a deadly toll. Many of the Aboriginal people in cities live in substandard housing and lack adequate health care. The unemployment rate among Aborigines is six times the national average, while those who are fortunate enough to have jobs earn only about half the average national wage. The results have been predictable: alienation, racial tensions, poverty, and unemployment.

While Australia's native people suffered with the arrival of colonists, the white population grew slowly and steadily as more and more people arrived from the United Kingdom. By the late 1850s, six separate British colonies (some of which were founded by "free" settlers), had taken root on the island continent. While there still were only about 400,000 white settlers, there were an estimated 13 million sheep— jumbucks as they are known in Australian slang, for it had quickly become apparent that the country was well suited to production of wool and mutton.

MODERN ERA

On January 1, 1901, the new Commonwealth of Australia was proclaimed in Sydney. New Zealand joined the six other colonies of the Commonwealth of Australia: New South Wales in 1786; Tasmania, then Van Diemen's Land, in 1825; Western Australia in 1829; South Australia in 1834; Victoria in 1851; and Queensland. The six former colonies, now refashioned as states united in a political federation that can best be described as a cross between the British and American political systems. Each state has its own legislature, head of government, and courts, but the federal government is ruled by an elected prime minister, who is the leader of the party that wins the most seats in any general election. As is the case in the United States, Australia's federal government consists of a bicameral legislature—a 72-member Senate and a 145-member House of Representatives. However, there are some important differences between the Australian and American systems of government. For one thing, there is no separation of legislative and executive powers in Australia. For another, if the governing party loses a "vote of confidence" in the Australian legislature, the prime minister is obliged to call a general election.

King George V of England was on hand to formally open the new federal parliament at Melbourne (the national capital was moved in 1927 to a planned city called Canberra, which was designed by American architect Walter Burley Griffin). That same year, 1901, saw the passage by the new Australian parliament of the restrictive immigration law that effectively barred most Asians and other "colored" people from entering the country and ensured that Australia would remain predominantly white for the next 72 years. Ironically, despite its discriminatory immigration policy, Australia proved to be progressive in at least one important regard: women were granted the vote in 1902, a full 18 years before their sisters in the United States. Similarly, Australia's organized labor movement took advantage of its ethnic solidarity and a shortage of workers to press for and win a range of social welfare benefits several decades before workers in England, Europe, or North America. To this day, organized labor is a powerful force in Australian society, far more so than is the case in the United States.

In the beginning, Australians mainly looked west to London for commerce, defense, political, and cultural guidance. This was inevitable given that the majority of immigrants continued to come from Britain; Australian society has always had a distinctly British flavor. With Britain's decline as a world power in the years following World War I, Australia drew ever closer to the United States. As Pacific-rim neighbors with a common cultural ancestry, it was inevitable that trade between Australia and the United States would expand as transportation technology improved. Despite ongoing squabbles over tariffs and foreign policy matters, American books, magazines, movies, cars, and other consumer goods began to flood the Australian market in the 1920s. To the dismay of Australian nationalists, one spinoff of this trend was an acceleration of the "Americanization of Australia." This process was slowed only somewhat by the hardships of the Great Depression of the 1930s, when unemployment soared in both countries. It accelerated again when Britain granted former colonies such as Australia and Canada full control over their own external affairs in 1937 and Washington and Canberra moved to establish formal diplomatic relations.

As a member of the British Commonwealth, Australia and America became wartime allies after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Most Australians felt that with Great Britain reeling, America offered the only hope of fending off Japanese invasion. Australia became the main American supply base in the Pacific war, and about one million American G.I.s were stationed there or visited the country in the years 1942 to 1945. As a nation considered vital to U.S. defense, Australia was also included in the lend-lease program, which made available vast quantities of American supplies with the condition that they be returned after the war. Washington policymakers envisioned that this wartime aid to Australia also would pay huge dividends through increased trade between the two countries. The strategy worked; relations between the two nations were never closer. By 1944, the United States enjoyed a huge balance of payments surplus with Australia. Almost 40 percent of that country's imports came from the United States, while just 25 percent of exports went to the United States. With the end of the war in the Pacific, however, old antagonisms resurfaced. A primary cause of friction was trade; Australia clung to its imperial past by resisting American pressure for an end to the discriminatory tariff policies that favored its traditional Commonwealth trading partners. Nonetheless, the war changed the country in some fundamental and profound ways. For one, Australia was no longer content to allow Britain to dictate its foreign policy. Thus when the establishment of the United Nations was discussed at the San Francisco Conference in 1945, Australia rejected its former role as a small power and insisted on "middle power" status.

In recognition of this new reality, Washington and Canberra established full diplomatic relations in 1946 by exchanging ambassadors. Meanwhile, at home Australians began coming to grips with their new place in the post-war world. A heated political debate erupted over the future direction of the country and the extent to which foreign corporations should be allowed to invest in the Australian economy. While a vocal segment of public opinion expressed fear of becoming too closely aligned with the United States, the onset of the Cold War dictated otherwise. Australia had a vested interest in becoming a partner in American efforts to stem the spread of communism in Southeast Asia, which lies just off the country's northern doorstep. As a result, in September 1951 Australia joined the United States and New Zealand in the ANZUS defense treaty. Three years later, in September 1954, the same nations became partners with Britain, France, Pakistan, the Philippines, and Thailand in the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), a mutual defense organization which endured until 1975.

From the mid-1960s onward, both of Australia's major political parties, Labor and Liberal, have supported an end to discriminatory immigration policies. Changes to these policies have had the effect of turning Australia into something of a Eurasian melting pot; 32 percent of immigrants now come from less-developed Asian countries. In addition, many former residents of neighboring Hong Kong relocated to Australia along with their families and their wealth in anticipation of the 1997 reversion of the British Crown colony to Chinese control.

It comes as no surprise that demographic diversification has brought with it changes in Australia's economy and traditional patterns of international trade. An ever-increasing percentage of this commerce is with the booming Pacific-rim nations such as Japan, China, and Korea. The United States still ranks as Australia's second largest trading partner— although Australia no longer ranks among America's top 25 trading partners. Even so, Australian American relations remain friendly, and American culture exerts a profound impact on life Down Under.

THE FIRST AUSTRALIANS AND NEW ZEALANDERS IN AMERICA

Although Australians and New Zealanders have a recorded presence of almost 200 years on American soil, they have contributed minimally to the total immigration figures in the United States. The 1970 U.S. Census counted 82,000 Australian Americans and New Zealander Americans, which represents about 0.25 percent of all ethnic groups. In 1970, less than 2,700 immigrants from Australia and New Zealand entered the United States—only 0.7 percent of the total American immigration for that year. Data compiled by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service indicates that about 64,000 Australians came to the United States in the 70 years from 1820 to 1890—an average of just slightly more than 900 per year. The reality is that Australia and New Zealand have always been places where more people move to rather than leave. While there is no way of knowing for certain, history suggests that most of those who have left the two countries for America over the years have done so not as political or economic refugees, but rather for personal or philosophical reasons.

Evidence is scarce, but what there is indicates that beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, most Australians and New Zealanders who immigrated to America settled in and around San Francisco, and to a lesser extent Los Angeles, those cities being two of the main west coast ports of entry. (It is important to remember, however, that until 1848 California was not part of the United States.) Apart from their peculiar clipped accents, which sound vaguely British to undiscerning North American ears, Australians and New Zealanders have found it easier to fit into American society than into British society, where class divisions are much more rigid and as often as not anyone from "the colonies" is regarded as a provincial philistine.

PATTERNS OF IMMIGRATION

There is a long, albeit spotty, history of relations between Australia and New Zealand and the United States, one that stretches back to the very beginnings of British exploration. But it was really the California gold rush in January 1848 and a series of gold strikes in Australia in the early 1850s that opened the door to a large-scale flow of goods and people between the two countries. News of gold strikes in California was greeted with enthusiasm in Australia and New Zealand, where groups of would-be prospectors got together to charter ships to take them on the 8,000-mile voyage to America.

Thousands of Australians and New Zealanders set off on the month-long transpacific voyage; among them were many of the ex-convicts who had been deported from Great Britain to the colony of Australia. Called "Sydney Ducks," these fearsome immigrants introduced organized crime into the area and caused the California legislature to try to prohibit the entry of ex-convicts. Gold was but the initial attraction; many of those who left were seduced upon their arrival in California by what they saw as liberal land ownership laws and by the limitless economic prospects of life in America. From August 1850 through May 1851, more than 800 Aussies sailed out of Sydney harbor bound for California; most of them made new lives for themselves in America and were never to return home. On March 1, 1851, a writer for the Sydney Morning Herald decried this exodus, which had consisted of "persons of a better class, who have been industrious and thrifty, and who carry with them the means of settling down in a new world as respectable and substantial settlers."

When the Civil War raged in America from 1861 to 1865, immigration to the United States all but dried up; statistics show that from January 1861 to June 1870 just 36 Australians and New Zealanders made the move across the Pacific. This situation changed in the late 1870s when the American economy expanded following the end of the Civil War, and American trade increased as regular steamship service was inaugurated between Melbourne and Sydney and ports on the U.S. west coast. Interestingly, though, the better the economic conditions were at home, the more likely Australians and New Zealanders seem to have been to pack up and go. When times were tough, they tended to stay home, at least in the days before transpacific air travel. Thus, in the years between 1871 and 1880 when conditions were favorable at home, a total of 9,886 Australians immigrated to the United States. During the next two decades, as the world economy faltered, those numbers fell by half. This pattern continued into the next century.

Entry statistics show that, prior to World War I, the vast majority of Australians and New Zealanders who came to America did so as visitors en route to England. The standard itinerary for travelers was to sail to San Francisco and see America while journeying by rail to New York. From there, they sailed on to London. But such a trip was tremendously expensive and although it was several weeks shorter than the mind-numbing 14,000-mile ocean voyage to London, it was still difficult and time-consuming. Thus only well-to-do travelers could afford it.

The nature of relations between Australians and New Zealanders with America changed dramatically with the 1941 outbreak of war with Japan. Immigration to the United States, which had dwindled to about 2,400 persons during the lean years of the 1930s, jumped dramatically in the boom years after the war. This was largely due to two important factors: a rapidly expanding U.S. economy, and the exodus of 15,000 Australian war brides who married U.S. servicemen who had been stationed in Australia during the war.

Statistics indicate that from 1971 to 1990 more than 86,400 Australians and New Zealanders arrived in the United States as immigrants. With few exceptions, the number of people leaving for the United States grew steadily in the years between 1960 and 1990. On average, about 3,700 emigrated annually during that 30-year period. Data from the 1990 U.S. Census, however, indicates that just over 52,000 Americans reported having Australian or New Zealander ancestry, which represents less than 0.05 percent of the U.S. population and ranks them ninety-seventh among ethnic groups residing in the United States. It is unclear whether all of those 34,400 missing persons returned home, migrated elsewhere, or simply did not bother to report their ethnic origin. One possibility, which seems to be borne out by Australian and New Zealander government statistics, is that many of those who have left those countries for the United States have been people born elsewhere—that is, immigrants who moved on when they did not find life in Australia or New Zealand to their liking. In 1991, for example, 29,000 Australians left the country permanently; 15,870 of that number were "former settlers," meaning that the rest were presumably native-born. Some members of both groups almost certainly came to the United States, but it is impossible to say how many because of the dearth of reliable data on Australian and New Zealander immigrants in the United States, where they live or work, or what kind of lifestyles they lead.

What is apparent from the numbers is that for whatever reason the earlier pattern of staying in their homeland during hard times has been reversed; now whenever the economy slumps, more individuals are apt to depart for America in search of what they hope are better opportunities. During the 1960s, just over 25,000 immigrants from Australia and New Zealand arrived in the United States; that figure jumped to more than 40,000 during the 1970s, and more than 45,000 during the 1980s. In the late 1980s and early 1990s a deep worldwide recession hit the resource-based economies of Australia and New Zealand hard, resulting in high unemployment and hardship, yet immigration to the United States remained steady at about 4,400 per year. In 1990, that number jumped to 6,800 and the following year to more than 7,000. By 1992, with conditions improving at home, the number dropped to about 6,000. Although U.S. Immigration and Naturalization service data for the period does not offer a gender or age breakdown, it does indicate that the largest group of immigrants (1,174 persons) consisted of homemakers, students, and unemployed or retired persons.

SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

About all that can be said for certain is that Los Angeles has become the favorite port of entry into the country. Laurie Pane, president of the 22-chapter Los Angeles-based Australian American Chambers of Commerce (AACC), suspects that as many as 15,000 former Australians live in and around Los Angeles. Pane surmises that there may be more Australians living in the United States than statistics indicate, though: "Australians are scattered everywhere across the country. They're not the sort of people to register and stay put. Australians aren't real joiners, and that can be a problem for an organization like the AACC. But they're convivial. You throw a party, and Australians will be there."

Pane's conclusions are shared by other business people, academics, and journalists involved with the Australian or New Zealander American community. Jill Biddington, executive director of the Australia Society, a New York-based Australian American friendship organization with 400 members in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut notes that without reliable data, she can only guess that the majority live in California because it is similar to their homeland in terms of lifestyle and climate.

Dr. Henry Albinski, director of the Australia-New Zealand studies center at Pennsylvania State University, theorizes that because their numbers are few and scattered, and because they are neither poor nor rich, nor have they had to struggle, they simply do not stand out—"there aren't stereotypes at either end of the spectrum." Similarly, Neil Brandon, editor of a biweekly newsletter for Australians, The Word from Down Under, says he has seen "unofficial" estimates that place the total number of Australians in the United States at about 120,000. "A lot of Australians don't show up in any legitimate census data," says Brandon. Although he has only been publishing his newsletter since the fall of 1993 and has about 1,000 subscribers all across the country, he has a firm sense of where his target audience is concentrated. "Most Aussies in the U.S. live in the Los Angeles area, or southern California," he says. "There are also fair numbers living in New York City, Seattle, Denver, Houston, Dallas-Forth Worth, Florida, and Hawaii. Australians aren't a tightly knit community. We seem to dissolve into American society."

According to Harvard professor Ross Terrill, Australians and New Zealanders have a great deal in common with Americans when it comes to outlook and temperament; both are easy going and casual in their relationships with others. Like Americans, they are firm believers in their right to the pursuit of individual liberty. He writes that Australians "have an anti-authoritarian streak that seems to echo the contempt of the convict for his keepers and betters." In addition to thinking like Americans, Australians and New Zealanders do not look out of place in most American cities. The vast majority who immigrate are Caucasian, and apart from their accents, there is no way of picking them out of a crowd. They tend to blend in and adapt easily to the American lifestyle, which in America's urban areas is not all that different from life in their homeland.

A CCULTURATION AND A SSIMILATION

Australians and New Zealanders in the United States assimilate easily because they are not a large group and they come from advanced, industrialized areas with many similarities to the United States in language, culture, and social structure. Data about them, however, must be extrapolated from demographic information compiled by the Australian and New Zealander governments. Indications are that they live a lifestyle strikingly similar to that of many Americans and it seems reasonable to assume that they continue to live much as they always have. Data show that the average age of the population—like that of the United States and most other industrialized nations—is growing older, with the median age in 1992 at about 32 years.

Also, there has been a dramatic increase in recent years in the number of single-person and two-person households. In 1991, 20 percent of Australian households had just one person, and 31 percent had but two. These numbers are a reflection of the fact that Australians are more mobile than ever before; young people leave home at an earlier age, and the divorce rate now stands at 37 percent, meaning that 37 of every 100 marriages end in divorce within 30 years. While this may seem alarmingly high, it lags far behind the U.S. divorce rate, which is the world's highest at 54.8 percent. Australians and New Zealanders tend to be conservative socially. As a result, their society still tends to be male-dominated; a working father, stay-at-home mother, and one or two children remains a powerful cultural image.

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

Australian historian Russell Ward sketched an image of the archetypal Aussie in a 1958 book entitled The Australian Legend . Ward noted that while Aussies have a reputation as a hard-living, rebellious, and gregarious people, the reality is that, "Far from being the weather-beaten bushmen of popular imagination, today's Australian belongs to the most urbanized big country on earth." That statement is even more true today than it was when it was written almost 40 years ago. But even so, in the collective American mind, at least, the old image persists. In fact, it was given a renewed boost by the 1986 movie Crocodile Dundee , which starred Australian actor Paul Hogan as a wily bushman who visits New York with hilarious consequences.

Apart from Hogan's likeable persona, much of the fun in the film stemmed from the juxtaposition of American and Aussie cultures. Discussing the popularity of Crocodile Dundee in the Journal of Popular Culture (Spring 1990), authors Ruth Abbey and Jo Crawford noted that to American eyes Paul Hogan was Australian "through and through." What is more, the character he played resonated with echoes of Davy Crockett, the fabled American woodsman. This meshed comfortably with the prevailing view that Australia is a latter-day version of what American once was: a simpler, more honest and open society. It was no accident that the Australian tourism industry actively promoted Crocodile Dundee in the United States. These efforts paid off handsomely, for American tourism jumped dramatically in the late 1980s, and Australian culture enjoyed an unprecedented popularity in North America.

INTERACTIONS WITH OTHER ETHNIC GROUPS

Australian and New Zealander society from the beginning has been characterized by a high degree of racial and ethnic homogeneity. This was mainly due to the fact that settlement was almost exclusively by the British, and restrictive laws for much of the twentieth century limited the number of non-white immigrants. Initially, Aboriginals were the first target of this hostility. Later, as other ethnic groups arrived, the focus of Australian racism shifted. Chinese goldminers were subject to violence and attacks in the mid-nineteenth century, the 1861 Lambing Riots being the best known example. Despite changes in the country's immigration laws that have allowed millions of non-whites into the country in recent years, an undercurrent of racism continues to exist. Racial tensions have increased. Most of the white hostility has been directed at Asians and other visible minorities, who are viewed by some groups as a threat to the traditional Australian way of life.

There is virtually no literature or documentation on the interaction between Australians and other ethnic immigrant groups in the United States. Nor is there any history of the relationship between Aussies and their American hosts. This is not surprising, given the scattered nature of the Australian presence here and the ease with which Aussies have been absorbed into American society.

CUISINE

It has been said that the emergence of a distinctive culinary style in recent years has been an unexpected (and much welcomed) byproduct of a growing sense of nationalism as the country moved away from Britain and forged its own identity—largely a result of the influence of the vast number of immigrants who have come into the country since immigration restrictions were eased in 1973. But even so, Australians and New Zealanders continue to be big meat eaters. Beef, lamb, and seafood are standard fare, often in the form of meat pies, or smothered in heavy sauces. If there is a definitive Australian meal, it would be a barbecue grilled steak or lamb chop.

Two dietary staples from earlier times are damper, an unleavened type of bread that is cooked over a fire, and billy tea, a strong, robust hot drink that is brewed in an open pot. For dessert, traditional favorites include peach melba, fruit-flavored ice creams, and pavola, a rich meringue dish that was named after a famous Russian ballerina who toured the country in the early twentieth century.

Rum was the preferred form of alcohol in colonial times. However, tastes have changed; wine and beer are popular nowadays. Australia began developing its own domestic wine industry in the early nineteenth century, and wines from Down Under today are recognized as being among the world's best. As such, they are readily available at liquor stores throughout the United States, and are a tasty reminder of life back home for transplanted Aussies. On a per capita basis, Aussies drink about twice as much wine each year as do Americans. Australians also enjoy their ice cold beer, which tends to be stronger and darker than most American brews. In recent years, Australian beer has earned a small share of the American market, in part no doubt because of demand from Aussies living in the United States.

TRADITIONAL COSTUMES

Unlike many ethnic groups, Australians do not have any unusual or distinctive national costumes. One of the few distinctive pieces of clothing worn by Australians is the wide-brimmed khaki bush hat with the brim on one side turned up. The hat, which has sometimes been worn by Australian soldiers, has become something of a national symbol.

DANCES AND SONGS

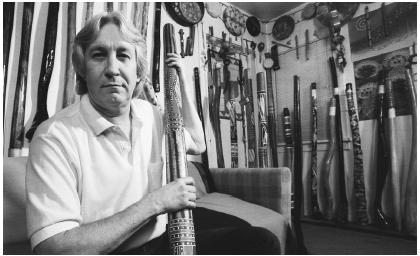

When most Americans think of Australian music, the first tune that springs to mind tends to be "Waltzing Matilda." But Australia's musical heritage is long, rich, and varied. Their isolation from western cultural centers such as London and New York has resulted, particularly in music and film, in a vibrant and highly original commercial style.

The traditional music of white Australia, which has its roots in Irish folk music, and "bush dancing," which has been described as similar to square-dancing without a caller, are also popular. In recent years, home-grown pop vocalists such as Helen Reddy, Olivia Newton-John (English-born but raised in Australia), and opera diva Joan

HOLIDAYS

Being predominantly Christian, Australian Americans and New Zealander Americans celebrate most of the same religious holidays that other Americans do. However, because the seasons are reversed in the Southern Hemisphere, Australia's Christmas occurs in midsummer. For that reason, Aussies do not share in many of the same yuletide traditions that Americans keep. After church, Australians typically spend December 25 at the beach or gather around a swimming pool, sipping cold drinks.

Secular holidays that Australians everywhere celebrate include January 26, Australia Day—the country's national holiday. The date, which commemorates the 1788 arrival at Botany Bay of the first convict settlers under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, is akin to America's Fourth of July holiday. Another important holiday is Anzac Day, April 25. On this day, Aussies everywhere pause to honor the memory of the nation's soldiers who died in the World War I battle at Gallipoli.

L ANGUAGE

English is spoken in Australia and New Zealand. In 1966, an Australian named Afferbeck Lauder published a tongue-in-cheek book entitled, Let Stalk Strine , which actually means, "Let's Talk Australian" ("Strine" being the telescoped form of the word Australian). Lauder, it later turned out, was discovered to be Alistair Morrison, an artist-turned-linguist who was poking good-natured fun at his fellow Australians and their accents—accents that make lady sound like "lydy" and mate like "mite."

On a more serious level, real-life linguist Sidney Baker in his 1970 book The Australian Language did what H. L. Mencken did for American English; he identified more than 5,000 words or phrases that were distinctly Australian.

GREETINGS AND COMMON EXPRESSIONS

A few words and expressions that are distinctively "Strine" are: abo —an Aborigine; ace —excellent; billabong —a watering hole, usually for livestock; billy —a container for boiling water for tea; bloke —a man, everybody is a bloke; bloody —the all-purpose adjective of emphasis; bonzer —great, terrific; boomer —a kangaroo; boomerang —an Aboriginal curved wooden weapon or toy that returns when thrown into the air; bush —the Outback; chook —a chicken; digger —an Aussie soldier; dingo —a wild dog; dinki-di —the real thing; dinkum, fair dinkum — honest, genuine; grazier —a rancher; joey —a baby kangaroo; jumbuck —a sheep; ocker —a good, ordinary Aussie; Outback —the Australian interior; Oz —short for Australia; pom —an English person; shout —a round of drinks in a pub; swagman —a hobo or bushman; tinny —a can of beer; tucker —food; ute —a pickup or utility truck; whinge —to complain.

F AMILY AND C OMMUNITY D YNAMICS

Again, information about Australian or New Zealander Americans must be extrapolated from what is known about the people who reside in Australia and New Zealand. They are an informal, avid outdoor people with a hearty appetite for life and sports. With a temperate climate all year round, outdoor sports such as tennis, cricket, rugby, Australianrules football, golf, swimming, and sailing are popular both with spectators and participants. However, the grand national pastimes are somewhat less strenuous: barbecuing and sun worshipping. In fact, Australians spend so much time in the sun in their backyards and at the beach that the country has the world's highest rate of skin cancer. Although Australian and New Zealander families have traditionally been headed by a male breadwinner with the female in a domestic role, changes are occurring.

R ELIGION

Australian Americans and New Zealander Americans are predominantly Christian. Statistics suggests that Australian society is increasingly secular, with one person in four having no religion (or failing to respond to the question when polled by census takers). However, the majority of Australians are affiliated with two major religious groups: 26.1 percent are Roman Catholic, while 23.9 percent are Anglican, or Episcopalian. Only about two percent of Australians are non-Christian, with Muslims, Buddhists, and Jews comprising the bulk of that segment. Given these numbers, it is reasonable to assume that for those Australian emigrants to the United States who are churchgoers, a substantial majority are almost certainly adherents to the Episcopalian or Roman Catholic churches, both of which are active in the United States.

E MPLOYMENT AND E CONOMIC T RADITIONS

It is impossible to describe a type of work or location of work that characterizes Australian Americans or New Zealander Americans. Because they have been and remain so widely scattered throughout the United States and so easily assimilated into American society, they have never established an identifiable ethnic presence in the United States. Unlike immigrants from more readily discernable ethnic groups, they have not established ethnic communities, nor have they maintained a separate language and culture. Largely due to that fact, they have not adopted characteristic types of work, followed similar paths of economic development, political activism, or government involvement; they have not been an identifiable segment of the U.S. military; and they have not been identified as having any health or medical problems specific to Australian Americans or New Zealander Americans. Their similarity in most respects to other Americans has made them unidentifiable and virtually invisible in these areas of American life. The one place the Australian community is flourishing is on the information superhighway. There are Australian groups on several online services such as CompuServe (PACFORUM). They also come together over sporting events, such as the Australian rules football grand final, the rugby league grand final, or the Melbourne Cup horse race, which can now be seen live on cable television or via satellite.

P OLITICS AND G OVERNMENT

There is no history of relations between Australians or New Zealanders in the United States with the Australian or New Zealand governments. Unlike many other foreign governments, they have ignored their former nationals living overseas. Those who are familiar with the situation, say there is evidence that this policy of benign neglect has begun to change. Various cultural organizations and commercial associations sponsored directly or indirectly by the government are now working to encourage Australian Americans and American business representatives to lobby state and federal politicians to be more favorably disposed toward Australia. As yet, there is no literature or documentation on this development.

I NDIVIDUAL AND G ROUP C ONTRIBUTIONS

ENTERTAINMENT

Paul Hogan, Rod Taylor (movie actors); Peter Weir (movie director); Olivia Newton-John, Helen Reddy, and Rick Springfield (singers).

MEDIA

Rupert Murdoch, one of America's most powerful media magnates, is Australian-born; Murdoch owns a host of important media properties, including the Chicago Sun Times , New York Post , and the Boston Herald newspapers, and 20th Century-Fox movie studios.

SPORTS

Greg Norman (golf); Jack Brabham, Alan Jones (motor car racing); Kieren Perkins (swimming); and Evonne Goolagong, Rod Laver, John Newcombe (tennis).

WRITING

Germaine Greer (feminist); Thomas Keneally (novelist, winner of the 1983 Booker Prize for his book Schindler's Ark , which was the basis for Stephen Spielberg's 1993 Oscar winning film Schindler's List ), and Patrick White (novelist, and winner of the 1973 Nobel Prize for Literature).

M EDIA

The Word from Down Under: The Australian Newsletter.

Address: P.O. Box 5434, Balboa Island, California 92660.

Telephone: (714) 725-0063.

Fax: (714) 725-0060.

RADIO

KIEV-AM (870).

Located in Los Angeles, this is a weekly program called "Queensland" aimed mainly at Aussies from that state.

O RGANIZATIONS AND A SSOCIATIONS

American Australian Association.

This organization encourages closer ties between the United States and Australia.

Contact: Michelle Sherman, Office Manager.

Address: 1251 Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York 10020.

150 East 42nd Street, 34th Floor, New York, New York 10017-5612.

Telephone: (212) 338-6860.

Fax: (212) 338-6864.

E-mail: Ameraust@mindspring.com.

Online: http://www.australia-online.com/aaa.html .

Australia Society.

This is primarily a social and cultural organization that fosters closer ties between Australia and the United States. It has 400 members, primarily in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut.

Contact: Jill Biddington, Executive Director.

Address: 630 Fifth Avenue, Fourth Floor, New York, New York 10111.

Telephone: (212) 265-3270.

Fax: (212) 265-3519.

Australian American Chamber of Commerce.

With 22 chapters around the country, the organization promotes business, cultural, and social relations between the United States and Australia.

Contact: Mr. Laurie Pane, President.

Address: 611 Larchmont Boulevard, Second Floor, Los Angeles, California 90004.

Telephone: (213) 469-6316.

Fax: (213) 469-6419.

Australian-New Zealand Society of New York.

Seeks to expand educational and cultural beliefs.

Contact: Eunice G. Grimaldi, President.

Address: 51 East 42nd Street, Room 616, New York, New York 10017.

Telephone: (212) 972-6880.

Melbourne University Alumni Association of North America.

This association is primarily a social and fund raising organization for graduates of Melbourne University.

Contact: Mr. William G. O'Reilly.

Address: 106 High Street, New York, New York 10706.

Sydney University Graduates Union of North America.

This is a social and fund raising organization for graduates of Sydney University.

Contact: Dr. Bill Lew.

Address: 3131 Southwest Fairmont Boulevard, Portland, Oregon. 97201.

Telephone: (503) 245-6064

Fax: (503) 245-6040.

M USEUMS AND R ESEARCH C ENTERS

Asia Pacific Center (formerly Australia-New Zealand Studies Center).

Established in 1982, the organization establishes exchange programs for undergraduate students, promotes the teaching of Australian-New Zealand subject matter at Pennsylvania State University, seeks to attract Australian and New Zealand scholars to the university, and assists with travel expenses of Australian graduate students studying there.

Contact: Dr. Henry Albinski, Director.

Address: 427 Boucke Bldg., University Park, PA 16802.

Telephone: (814) 863-1603.

Fax: (814) 865-3336.

E-mail: pac9@psu.edu.

Australian Studies Association of North America.

This academic association promotes teaching about Australia and the scholarly investigation of Australian topics and issues throughout institutions of higher education in North America.

Contact: Dr. John Hudzik, Associate Dean.

Address: College of Social Sciences, Michigan State University, 203 Berkey Hall, East Lansing, Michigan. 48824.

Telephone: (517) 353-9019.

Fax: (517) 355-1912.

E-mail: Hudzik@ssc.msu.edu.au.

Edward A. Clark Center for Australian Studies.

Established in 1988, this center was named after a former U.S. Ambassador to Australia from 1967 to 1968; it conducts teaching programs, research projects, and international outreach activities that focus on Australian matters and on U.S.-Australia relations.

Contact: Dr. John Higley, Director.

Address: Harry Ransom Center 3362, University of Texas, Austin, Texas 78713-7219.

Telephone: (512) 471-9607.

Fax: (512) 471-8869.

Online: http://www.utexas.edu/depts/cas/ .

S OURCES FOR A DDITIONAL S TUDY

Arnold, Caroline. Australia Today . New York: Franklin Watts, 1987.

Australia , edited by George Constable, et al. New York: Time-Life Books, 1985.

Australia, edited by Robin E. Smith. Canberra: Australian Government Printing Service, 1992.

Australians in America: 1876-1976 , edited by John Hammond Moore. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 1977.

Bateson, Charles. Gold Fleet for California: Forty-Niners from Australia and New Zealand. [Sydney], 1963.

Forster, John. Social Process in New Zealand. Revised edition, 1970.

Hughes, Robert. The Fatal Shore: A History of The Transportation of Convicts to Australia, 1787-1868 . New York: Alfred Knopf, 1987.

Renwick, George W. Interact: Guidelines for Australians and North Americans. Chicago: Intercultural Press, 1980.

Source : http://www.everyculture.com/multi/A-Br/Australian-and-New-Zealander-Americans.html