O VERVIEW

Bosnia-Herzegovina, located on the Balkan peninsula in Eastern Europe, is a republic of the former Yugoslavia. The northern portion, Bosnia, is mountainous and wooded, while Herzegovina, to the south, is primarily flatland. The republic has a land area of 19,741 square miles (51,129 square kilometers) and a population of 2.6 million, down from 4.3 million before the war of the 1990s. Bosnia's capital is Sarajevo, the site of the 1984 Winter Olympics. Mostar is the capital of Herzegovina. Almost 95 percent of the population speaks Bosnian, also called Serbo-Croatian. Bosnians descended from Slavic settlers who came to the area in the early Middle Ages. The population includes Catholic Bosnian Croats (17 percent); Eastern Orthodox Bosnian Serbs (31 percent); and Bosnian Muslims (44 percent), whose ancestors converted from Christianity centuries ago. Some historians have pointed out that the residents of Bosnia are ethnically much the same and have chosen to identify as Croats or Serbs primarily for religious and political reasons.

From 1992 until 1995, Bosnian Serbs waged a war against non-Serbs. The war ended with the Dayton Peace Accord, which recognizes Bosnia-Herzegovina as a single state that is partitioned, with a Muslim-Croat federation given 51 percent of the area and a Serbian republic given 49 percent. The Bosnia-Herzegovina flag, adopted February 4, 1998, has a blue background with a yellow inverted triangle in the center. To the left of the triangle is a row of white stars in a line from the top edge to the bottom edge of the flag.

HISTORY

In the first few centuries A.D., the Roman Empire held Bosnia. After the empire disintegrated, various powers sought control of the land. Slavs were living in Bosnia by the seventh century, and by the tenth century they had an independent state. In the ninth century, the two kingdoms of Serbia and Croatia were established.

Bosnia briefly lost its independence to Hungary in the twelfth century, but regained it around 1180. It prospered and expanded under three especially powerful rulers: Ban Kulin, who reigned from 1180 to 1204; Ban Stephen Kotromanic, who ruled from 1322 to 1353; and King Stephen Tvrtko, who reigned from 1353 to 1391. After Tvrtko's death, internal struggles weakened the nation. The neighboring Ottoman Turks were becoming increasingly aggressive, and they conquered Bosnia in 1463. For more than 400 years, Bosnia was an important province of the Ottoman Empire. Islam was the official religion, though non-Muslim faiths were allowed. Indeed, in the Ottoman era many Jews came from Spain, where they faced persecution or death at the hands of the Catholic Inquisition, to find a tolerant home in Bosnia.

By the nineteenth century, however, many Bosnians were dissatisfied with Ottoman rule. Clashes between peasants and landowners were frequent, and there was tension between Christians and Muslims. Foreign powers became interested in the region. At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, following the end of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), Austria-Hungary took over the administration of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Many Bosnian Muslims, who thought the new rulers favored Serbian interests, emigrated to Turkey and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. The Austro-Hungarian government formally annexed Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908. Nationalists in Serbia, who had hoped to make Bosnia-Herzegovina part of a great Serb nation, were outraged. In 1914, a Serb nationalist assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne in Sarajevo, thrusting the nations into World War I from 1914 to 1918. At the end of the war came the creation of the South Slav state, which together with Serbia became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Bosnia's Muslim Slavs were urged to register themselves as Serbs or Croats. Nazi Germany, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, invaded Yugoslavia in 1941. The Nazis set up a puppet Croatian state, incorporating all of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but persecuted and killed Serbs, Gypsies, and Jews, as well as Croats who opposed the regime. Yugoslav communist Josip Broz Tito led a multi-ethnic force against Germany, and at the end of World War II, he became premier of Yugoslavia. Under Tito's rule, Yugoslavia was a one-party dictatorship that restricted religious practice for 35 years.

MODERN ERA

After Tito's death in 1980, the presidents of the six republics and two autonomous regions ruled Yugoslavia by committee. The country suffered economic problems in the 1980s, and the decade was also marked by a rise in nationalism among its component republics. The Muslim-led government of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared its independence from Yugoslavia in March 1992. The following month, the United States and the European community recognized the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Interethnic fighting began as the Yugoslav National Army, under the leadership of Slobodan Milosevic, attacked Sarajevo. Milosevic, the leader of Serbia, sought to unite all Serbian lands and to purge the regions of non-Serb populations. Serbs, Croats, and Muslims fought to expand or keep their territories within Bosnia. By mid-1995, most of the country was in the hands of Bosnian Serbs who were accused of conducting "ethnic cleansing"—the systematic killing or expulsion of other ethnic groups. At the time the Dayton peace agreement was signed in December 1995, more than one million Bosnians remained displaced within the borders of the republic. At least one million more were living as refugees in 25 other countries, primarily in the neighboring republics of former Yugoslavia but also throughout Western Europe.

At the end of the twentieth century, the United Nations maintained a peacekeeping operation and arbitrates disputes in Bosnia. Since June 1995, the areas of control have changed frequently. The Muslim/Croat Federation reclaimed large amounts of territory in western Bosnia. In addition, Bosnian Serb forces took military control of two U.N. safe areas, Zepa and Srebrenica. In March of 1999, an international arbitration panel ruled that a 30-square-mile part of northern Bosnia around the town of Brcko would be a neutral community under international supervision, rather than a part of the Bosnian Serb Republic. Under authority of the Dayton agreement, the panel also dismissed Bosnian Serb President Nikola Poplasen, who resigned immediately.

THE FIRST BOSNIANS IN AMERICA

The first Serb immigrants came in the first half of the nineteenth century and helped settle the American West. Many were young men from the Dalmatian coast, where they had worked as sailors or fishermen. Once in the United States, many of them worked in fishing or shipping in cities such as San Francisco, New Orleans, and Galveston, Texas, where they worked in the fishing and shipping industries. Most of them married outside of their ethnic group. Accurate immigration figures for Bosnians are impossible to obtain. Until 1918 the U.S. Immigration Service counted Croatians from Dalmatia, Bosnia, and Herzegovina separately from other Croatians, who were classified as Slovenians. After 1918 Croatians were listed as Yugoslavs. Prior to 1993, data for immigration from Bosnia-Herzegovina was not available separately from Yugoslavia.

SIGNIFICANT IMMIGRATION WAVES

There were six waves of Serbian/Croatian immigration. The earliest occurred from 1820 to 1880. The largest wave of Yugoslav immigrants took place from 1880 to 1914, when approximately 100,000 Serbs arrived in the United States. Most were unskilled laborers who fled the Austro-Hungarian policies of forced assimilation. Croatian and Serbian immigrants were largely young, impoverished peasant men. In the United States they settled in the major industrial cities of the East and Midwest, working long hours at low-paying jobs.

The third wave happened between World War I and World War II. From 1921 to 1930, 49,064 immigrants arrived. These interwar years were times of Serbian nationalist fervor. The Yugoslav regime became increasingly dictatorial, ruling provinces through military governors. Immigrants sought freedom from ethnic oppression by coming to the United States. The number of immigrants dropped to 5,835 in the decade from 1931 to 1941, and then decreased to 1,576 during World War II when Germany controlled Yugoslavia. Immigration was further reduced during the postwar years when the Communist Party under Tito took over the country. The fourth wave was made up of displaced persons and war refugees from 1945 until 1965.

The fifth major surge began in the sixties, when 20,381 Yugoslavians immigrated, a surge that continued into the next decade with 30,540 more immigrants. During the years of Tito's rule, Yugoslavia received economic and diplomatic support from the United States. In the 1970s, the U.S. Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, went as far as to say that the United States would risk nuclear war on Yugoslavia's behalf. From 1981 to 1990, 19,200 Yugoslavians immigrated to the United States. These Croatian and Serbian immigrants were intellectuals, artists and professionals who adapted easily to life in the United States.

The sixth wave came as a response to disintegrating political stability after Bosnia declared its independence from Yugoslavia in 1992. These immigrants have primarily been Muslim, pushed out by Serbs fighting to create a Serb-only region. From 1991 to 1994, 11,500 immigrated. The number fell to 8,300 in 1995, then rose to 11,900 in 1996. In 1994, with the U.S. Census records listing Bosnians as a separate category, 337 refugees were granted permanent residence. There were an additional 3,818 refugees in 1995 and 6,246 in 1996. In 1996, 19,242 Bosnians filed for refugee status. Of these, 14,654 were eventually approved, and 1,939 were denied. Bosnian refugees settled into communities all over the United States. Most received help from charitable organizations, as well as aid from the immigrants who preceded them. In 1998, 88 Bosnians and Herzegovinans were winners of the DV-99 diversity lottery. The diversity lottery is conducted under the terms of Section 203(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act and makes available 50,000 permanent resident visas annually to persons from countries with low rates of immigration to the United States.

SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

Most Bosnian immigrants have settled quickly into long-established ethnic enclaves. Bosnian Serbs tend to settle with other Serbs and Bosnian Croats in local Croatian communities. Until the war in the 1990s, Bosnian Muslim immigrants had been so few in number that there was no Bosnian Muslim community into which they could integrate. They concentrated in urban areas, some of which now have significant Bosnian Muslim populations. In the Astoria section of New York City, for instance, Bosnian Muslims built a mosque that was dedicated in 1997.

Of the 258,000 Americans of Yugoslavian ancestry living in the United States in 1990, 37 percent lived in the West, 23 percent lived in the Northeast, 28 percent lived in the Midwest, and only 12 percent lived in the South. Cities with large Yugoslavian American populations included Chicago, New York, Newark, Detroit, St. Louis, Des Moines, Atlanta, Houston, Miami, and Jacksonville, Florida. According to the 1990 census, the highest concentration of Serbs, Croats, and Bosnian Muslims is in a neighborhood near 185th Street in eastern Cleveland.

Serbs and Croats have left their mark on many parts of the United States. Early Croatian immigrants prospered as merchants and fruit growers in California's Pajaro Valley. Croatians were among the first settlers of Reno, Nevada. New Orleans became a center of Croatian immigration in the early nineteenth century. The first Slavic ethnic society in the South was established in 1874 by a group of Croatians and Serbs.

Bosnian Americans who came as refugees after 1992 have settled in fast-growing enclaves in cities such as New York, St. Louis, St. Petersburg, Chicago, Salt Lake City and Waynesboro, Pennsylvania. In St. Louis, for example, the Bosnian population reached 8,000 in 1999; of these 7,000 are Muslims. In the early 1990s, there had been fewer than 1,000 Bosnians in St. Louis. In 1998, Bosnian immigrants arrived in St. Louis at a rate of 40 to 60 per week. About 5,000 Bosnians live in Salt Lake City, where an annual "Living Traditions Festival" includes Bosnian dance and music performances by the American Bosnian and Herzegovinian Association of Utah.

About 15,000 Bosnians live in the Queens borough of New York City. Most are refugees who were settled by religious or nonprofit groups. Bosnian American refugees are especially attracted to established ethnic communities because many refugees are separated from immediate family members. It often takes several years to reunite families, so the Bosnian community provides needed social support.

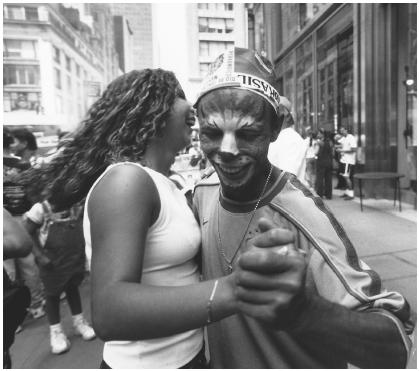

A CCULTURATION AND A SSIMILATION

Bosnian refugees face many challenges in the United States. They must start over, learning a new language, new customs, and new skills. One Bosnian American refugee described this adjustment to the St. Petersburg Times as "in some ways like being a blind man who wants to take care of himself but is powerless to do so." Since their immigration was not necessarily by choice, they often find the experience more overwhelming in comparison to immigrants who were eager to come here. Learning English is the first step that Bosnians take once they reach the United States, though many Bosnians speak several European languages. Established Bosnian communities offer services such as English-language classes, computer training classes, no-cost legal services, and instruction on understanding health insurance, buying a home, and managing other complicated aspects of American life. Established communities also usually provide a place for worship.

By 1999, more than one million Bosnia refugees remained in the United States even though the war ended in 1995. Many cannot return to Bosnia because of the boundaries of territories changed and their homes are in a divided country. Many are like Nijaz (pronounced nee-AHS) Hadzidedic (hah-jee-DED-ich), a Muslim Bosnian living in Memphis, Tennessee. Hadzidedic, a Bosnian journalist who was shot by Serbian soldiers during the war, came in 1994 as a refugee sponsored by a local Catholic charity. His brother and niece joined him in 1997. Hadzidedic found work in lower-status jobs such as security guard, factory worker, and bellhop. After he becomes a U.S. citizen, he plans to return to the Balkans and work as a translator.

Bosnian Americans often seek higher education and better employment opportunities. Many also Americanize their names, which are difficult for Americans to pronounce. Earlier immigrants often discovered with surprise that immigration officials had Americanized their names on the documents that admitted them to the country.

TRADITIONS, CUSTOMS, AND BELIEFS

Three main groups, Serbs, who are Eastern Orthodox, Crozts, who are Catholic, and Muslims who are Islamic, comprise Bosnia-Herzegovina's population. Each group has its distinct beliefs, traditions, and customs. Bosnian American communities have good informal networks of communication. Places of worship provide a gathering spot for religious activities as well as weddings, baptisms (for Croats and Serbs) and funerals.

Islamic culture dominated Bosnia for centuries. Modern Western culture penetrated Bosnia and Herzegovina only after Austria occupied the region in 1878. Gradually, Latin and Cyrillic scripts replaced Arabic script. After 1918, secular education began replacing Islamic schools, and education became available to women.

Almost all Bosnian family names end in "ic," which essentially means "child of," much like the English "John-son." Women's first names tend to end in "a" and "ica," pronounced EET-sa. Family names are often an indication of ethnicity. Sulejmanagic, for example, is a Muslim name, as are others containing such Islamic or Turkish roots as "hadj" or "bey," pronounced "beg." Children receive their father's last name. Hence, someone with an Islamic-sounding root in his or her last name may be presumed to be, at least by heritage, a Muslim.

PROVERBS

Bosnia has many proverbs derived from the three ethnic groups that make up its population. Here are a few that are known to all three groups: He who is late may gnaw the bones; A good rest is half the work; Complain to one who can help you; He who lies for you will lie against you; You can make peasant drunk on a glass of water and a gypsy violin.

CUISINE

The cuisine of Bosnia reflects influences from Central Europe, the Balkans, and the Middle East. Meat dishes of lamb, pork, and beef, typically small sausages called cevapcici (kabobs) or hamburger patties called pljeskavica are grilled with onions and served on a fresh somun, a thick pita bread. Cevapcici are made from ground meat and spices that are shaped into little cylinders, cooked on an open fire and served on an open platter. Another favorite is a Bosnian stew called bosanski lonac, which is a slow-roasted mixture of layers of meat and vegetables eaten with chunks of brown bread. It is usually served in a vaselike ceramic pot. Serbian meat and fish dishes are typically cooked first, then braised with vegetables such as tomatoes and green peppers.

Mediterranean and Middle Eastern influences are evident in aschinicas (pronounced ash-chee-neetsa-as), restaurants offering various kinds of cooked meat, filled vegetables called dolmas, kabobs, and salads, with Greek baklava for dessert. The filling most often consists of ground meat, rice, spices, and various kinds of chopped vegetables. Containers can be hollowed-out peppers, potatoes, or onions. Some dolmas are made from cabbage leaves, grapevine, kale, or some other leaf large enough and softened enough by cooking that it can be wrapped around the little ball made of the filling. When enough pieces are made, they are stacked in an amphora-shaped tureen that is then covered with its own lid or with a piece of parchment tightly tied around its neck. The dish is then cooked slowly on a low, covered fire.

Pita, pastry filled with meat or vegetables, is another distinctive Bosnian dish. In other parts of the former Yugoslavia, pitas that are meat-filled are called burek. Pita meat pie often is the final course of a meal or is served as a light supper on its own.

Orthodox Bosnians include special dishes in their Easter celebrations. In Orthodox tradition, after the midnight service, the congregation walks around the church seven times carrying candles, then goes home to a supper that includes hardboiled eggs that have been dyed and decorated, and Pasca, a round, sweet yeast cake filled with either sour cream or cottage cheese.

Homemade brandy, known as rakija in the former Yugoslavia but exported to the United States as slivovitz (plum brandy) or loza (grape brandy or grapa ), is the liquor of choice for men on most occasions. Women may opt instead for fruit juice. Popular nonalcoholic beverages other than fruit juices include Turkish-style coffee ( kahva, kafa or kava ), a thin yogurt drink called kefir, and a tea known as salep.

MUSIC

The arts were highly developed in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The three major ethnic groups contributed a great wealth of song, dance, literature, and poetry. The Serbian Bosnian American culture is centered around music. Choirs and tamburica orchestras have been a part of local communities since 1901, when the Gorski Vijenac (Mountain Wreath) choir of Pittsburgh was founded. The tamburica is a South Slavic stringed instrument much like a mandolin. It exists five different sizes and musical ranges. The Bosnian community in St. Louis holds an annual Tamburitza Extravanganza Festival where as many as twenty bands from all over the country perform. The Duquesne University Tamburitzans maintains a folklore institute and trains new performers.

Sviraj (pronounced svee-rye, with a rolled "r") is a popular group of ethnic Balkan musicians who preserve their heritage through performances that celebrate the music of Eastern Europe. Sviraj means "Play!" in Serbian and Croatian. The music has its roots in Serbia, Croatia, Macedonia, Bosnia, Dalmatia, and Romania.

TRADITIONAL COSTUMES

For centuries Bosnia was well known for having the widest variety of folk costumes of any region of the former Yugoslavia. Today, these outfits serve as stage costumes rather than street wear. Traditionally, older men wore breeches, a cummerbund, a striped shirt, a vest, and even a fez , a hat that was usually red. These garments were often colorful and richly embroidered. The typical women's costume was a fine linen blouse embroidered with floral or folk motifs, worn under a vest called a jelek that was cut low under the breast and made of velvet, embroidered with silver or gold thread. A colorful skirt was covered by an apron and worn on top of a white linen petticoat that showed beneath the skirt. The baggy trousers worn by women, called dimije, spread to all three ethnic groups as a folk costume, though each group wore different colors as specified by the Ottoman Empire. Dimije were rare on the streets of cities before World War II, but they were common in rural districts and among the older women within the cities. Traditional fashion lore dictated that you could tell how high in the mountains a woman's village was by how high on the ankles she tied her dimije to keep the hems out of the snow.

The devout Muslim women of Bosnia have not traditionally worn the chador familiar in fundamentalist Muslim countries. The chador is a garment that covers women from head to toes. Bosnian Muslim women instead wear head scarves and raincoats as symbolic substitutes for the chador , particularly on religious holidays.

DANCES AND SONGS

Music and dance reflect Bosnia's great diversity. During the years of Tito's rule, Bosnian amateur folklore groups, called cultural art societies, flourished throughout the region. They were required to perform the folk music and dances of all three major ethnic groups. Some such troupes also performed contemporary plays, modern dance, choral works, and ballet.

Bosnian music can be divided into rural and urban traditions. The rural tradition is characterized by such musical styles as ravne pjesme (flat song) of limited scale; ganga, an almost shouted polyphonic style; and other types of songs that may be accompanied on the shargija (a simple long-necked lute), the wooden flute, or the diple, a droneless bagpipe. The urban is more in the Turkish style, with its melismatic singing—more than one note per syllable— and accompaniment on the saz, a larger and more elaborate version of the shargija. Epic poems, an ancient tradition, are still sung to the sound of the gusle, a single-string bowed fiddle. While Bosnia's Jewish population was decimated by World War II, its influence remains apparent in folk songs sung in Ladino, a dialect descended from 15th-century Spanish.

In the 1990s, the influence of Western pop music and of new native pop music in a folkish style, played on the accordion, became apparent. But modern influences have not displaced sevdalinka. With a name derived from the Turkish word sevda (love), sevdalinka songs have been the dominant form of music in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Incorporating both Western and Eastern elements, these deeply emotional songs speak metaphorically and symbolically of love won and lost, much like American country western music.

Bosnia has one of the richest and yet least known of all the regional folk dance traditions of the former Yugoslavia. Dances range from the nijemo kolo, accompanied only by the sound of stamping feet and the clash of silver ornaments on the women's aprons, to line dances in which the sexes are segregated as they are in the Middle East, to Croatian and Serbian dances similar to those performed across the borders in their native regions. As with traditional music, however, these folk dances are losing popularity as modern European social dances and rock and roll steps gain favor.

HOLIDAYS

In addition to American holidays, Bosnian Americans observe their individual religions' holidays. The Serbian Orthodox Church uses the Julian calendar, which is 13 days behind the Gregorian one commonly used in the West. Serb Bosnian Americans follow this calendar for holidays. For example, Orthodox Christmas falls on January 7 rather than December 25. Eastern Orthodox Christian families also celebrate the Slava, or saint's name day, of each member of the family. Muslim Bosnian Americans follow Islam's holidays and calendar, including Ramadan, the month of ritual fasting. At the end of Ramadan, a period called Bajram, they exchange visits and small gifts during the three days. Croat Bosnian Americans observe Catholic holidays.

L ANGUAGE

The official language of Bosnia-Herzegovina is Bosnian, also called Serbo-Croatian. The language goes by different names because of the country's ethnic differences and rivalries. People in the Muslim-controlled sector call it Bosnian, those in Croat areas call it Croatian, and those in Serb areas refer to it as Serbian.

Bosnian belongs to the Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family and more specifically to the group of South Slavic languages, which includes Bulgarian, Macedonian, and Slovenian. It actually has a few words that are recognizably related to English. Bosnian "sin" is "son," and Bosnian "sestra" is "sister." Bosnian has many borrowed words from other European languages, English, Turkish, Arabic, and Persian.

Bosnian is written in either the Cyrillic or the Latin alphabet. Its letters are generally pronounced as they are in English, with certain exceptions. "C" is pronounced "ts"; "ác" is pronounced similar to "tch" but with a thinner sound, more like the thickened "t" in future; "

Bosnian Americans generally have little difficulty pronouncing English, although the "th" and "w" sounds may give them some trouble. They may also find some English verbs hard to understand. Bosnian uses fewer auxiliary verbs, such as "be" and "do" than English, and Bosnian speakers may be puzzled by questions in English, in which the auxiliary verb comes before the subject, as in "Did you eat?"

GREETINGS AND POPULAR EXPRESSIONS

During the war, one of the most frequently asked questions was, "Sta je tvoje ime?" (pronounced stah-yeah-tVOya) meaning "what is your name" in Bosnian, because the name was the major clue to ethnicity.

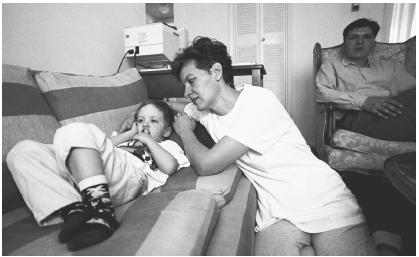

F AMILY AND C OMMUNITY D YNAMICS

In most Bosnian American families, both husband and wife work outside the home, but the wife still has primary responsibility for housework and cooking. In Bosnia, the effects off the wars of the twentieth century and migration away from rural areas after World War II have resulted in fewer extended families living together. But Bosnian Americans tend to live with extended family members, though this is likely to end as Bosnians acclimate to American culture and become more financially successful. Bosnian Muslims tend to have fewer relative connections already living in the United States, since prior to 1992 there were few Muslim immigrants. Polygamy as a Muslim custom last existed in Bosnia in the early 1950s, and then only in one isolated region of the country, Cazinska Krajina. Most Bosnian marriages follow the modern custom of love matches, and arranged marriage between families having largely disappeared. About a third of all urban marriages in Bosnia in recent decades have been between partners from different religious and ethnic backgrounds. Family size has been decreasing as education and prosperity have increased.

EDUCATION

The literacy rate in Bosnia prior to the civil war of 1992 was 92 percent. Education through the eighth grade was compulsory for both boys and girls, after which a student could opt for either a vocational trade school or a more academically oriented route. There were university faculties in the larger cities, along with a community college-type option called "workers' universities."

BIRTH AND BIRTHDAYS

Serbian Bosnian Americans choose a Kum or Kuma (female godparent) shortly after the birth of a child. The godparents name the child. Bosnian Americans celebrate birthdays with gifts and parties.

THE ROLE OF WOMEN

Many Bosnian American women refugees have lost everything and have become the heads of house-holds for the first time. They face the challenge of rebuilding their lives in a new country, adapting to a culture and language, while providing food, shelter, and education for themselves and their surviving relatives. Many were financially dependent on their spouses before the war, and they consequently have no marketable skills or entrepreneurial experience.

Traditionally, women played subservient roles in Yugoslavia's patriarchal families, especially in the country's remote mountainous regions. In the interwar period, laws codified women's subservient status. Industrialization and urbanization in the communist era changed traditional family patterns. This trend was most pronounced in the more developed northern and western urban areas. The number of women employed outside the home rose from 396,463 in 1948 to 2.4 million in 1985. As women began working away from home, they became more independent. In the 1980s, the percentage of women in low-level political and management positions was equal to that of men, but this was not the case for upper management positions.

Women accounted for 38 percent of Yugoslavia's nonagricultural labor force in 1987, up from 26 percent 30 years earlier. The participation of women in the Yugoslav work force varied dramatically according to region. In 1989 Yugoslav women worked primarily in cultural and social welfare, public services and public administration, and trade and catering. Almost all of Yugoslavia's elementary school teachers were women. A few women's groups have formed in the major cities of Bosnia, but the modern women's movement did not achieve significant power in the former Yugoslavia or its successor states.

WEDDINGS

In 1992, when the war started in Bosnia, approximately 40 percent of the registered marriages in urban centers were between ethnically mixed Bosnians. Ceremonies reflect this mix, often including traditions from both ethnic groups involved. The bride usually wears white and is attended by bridesmaids. Men wear capes. There are many flowers, and there is much drinking and dancing. The food includes Bosnian biscuits, a coffee cake-like bread with walnuts, raisins, and chocolate.

An Islamic tradition of giving hand-woven carpets ( kilims ) and knotted rugs lasted for centuries. The custom of giving a personally woven dowry rug, with the couple's initials and date of marriage, disappeared only in the 1990s.

INTERACTIONS WITH OTHER ETHNIC GROUPS

It is important to understand that the contributing basis of hostility among twentieth-century Bosnians has largely been due to economic reasons, not religious ones. As all three groups became more secular, religious-based conflict actually diminished. But economically and politically, Bosnian Muslim landowners were resented by Catholic Croats and Orthodox Christian Serbs. American Bosnians do not face the same political pressures, so the different ethnic communities coexist peacefully in American cities. Bosnian Americans often marry across ethnic lines, which gives them a powerful reason to stay in the United States. If people in a mixed marriage return to Bosnia, they are not accepted by either person's ethnic group.

R ELIGION

Many Bosnians treat their religion the same way many Americans do theirs, as something restricted to one day of church attendance and major religious holidays. The Yugoslav government discouraged religious fundamentalism, as did the religious community itself, reflecting years of accommodation between the religion and the Communist state. Religious affiliation in Yugoslavia, however, was closely linked with the politics of nationality. Centuries-old animosities among the Eastern Orthodox Serbs, the Roman Catholic Croats, and the Bosnian Muslims remained a divisive factor in the 1990s, though the basis was more economic power that religious fervor. There also was lingering resentment over forced conversions of Orthodox Serbs to Roman Catholicism by ultranationalist Croatian priests during World War II.

According to the 1990 U.S. census, there were 68 Serbian Orthodox churches in the United States and Canada with a membership of 67,000. Serbian Orthodox churches serve as a social center as well as a place of worship. Serbian Bosnian Americans celebrate a family's religious anniversary, the krsna slava, each year. Slava commemorates the conversion of the family's ancestors to Christianity in the ninth century, and on this day families feast and receive the visit of a priest. Bosnian Serbs also celebrate Easter with feasting and special ceremonies. Many Serbian Orthodox Bosnians continue the practice of using amulets against the "evil eye," a generalized concept of evil. Precautions against the evil eye include wearing garlic and wearing the mati, a blue amulet with an eye in the center.

E MPLOYMENT AND E CONOMIC T RADITIONS

Bosnian immigrants are very willing to work diligently at low-status jobs while they seek additional language skills and education. Most find work in their communities immediately, as bakers, factory workers, hotel housekeepers, and other types of service workers. Of the 6,499 Bosnian Americans who immigrated in 1996, 2,794 had occupations. Of employed Bosnian Americans, four percent had professional specialties, 26 percent were employed in service industries, and 51 percent were unskilled laborers. Many Bosnian American refugees are unable to pursue their former occupations in the United States because they do not speak English. Bosnian American doctors, lawyers, and other professionals often work for as little as five dollars an hour while they learn English in order to apply for their licenses. Some have improvised other solutions. The New York Daily News ran a story on a Bosnian refugee and former soccer star who now runs a cafe and has launched a weekly Bosnian newspaper, Sabah, published in Serbo-Croatian.

P OLITICS AND G OVERNMENT

Croatian and Serbian Americans organized labor unions and strikes for better working conditions as early as 1913. The oldest Croatian fraternal associations, Slavonian Illyrian Mutual Benevolent Society, founded in 1857 in San Francisco, and the United Slavonian Benevolent Association of New Orleans, provided financial help to families of injured immigrants. Croatian and Serbian Americans formed many groups dedicated to influencing policies of their homeland. In the United States, Croatian Americans have traditionally been strong supporters of the Democratic Party.

Bosnian Americans speak out about conditions in their former homeland. For example, in an interview on CNN's Larry King Live, professional basketball player Vlade Divac of the Sacramento Kings said Americans have been misled about the situation in Yugoslavia. Divac reported that his relations with some NBA players had been affected by his Serbian heritage.

RELATIONS WITH FORMER COUNTRY

The United States supported Yugoslavia under Tito's rule because Tito had broken with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. The United States provided economic and military assistance to prevent Soviet aggression in the area. But with the fall of communism and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia lost its strategic importance to the United States. When the war broke out in 1992, James Baker, secretary of state under President George Bush, was quoted as saying, "We don't have a dog in that fight." Eventually, however, the United States became involved in finding a peaceful solution to the civil strife in Bosnia. On November 21, 1995, the General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina (the Dayton-Paris Agreement) was concluded as a result of a United States-led peace initiative after three years of peacemaking efforts by the international community. When the Dayton Peace Accord was signed the following month. U.N. Secretary-General Boutros Boutros Ghali thanked U.S. President Bill Clinton for his role. The United States remains involved militarily and diplomatically in Bosnia and the former Yugoslavia.

I NDIVIDUAL AND G ROUP C ONTRIBUTIONS

Who's Who listings are rich with contributions from Serbian and Croatian Americans, encompassing all fields of endeavor. Most of these citations list Yugoslavia as a place of birth.

LITERATURE

Aleksandar Hemon was born in Sarajevo and currently lives in Chicago. He is primarily a writer of short fiction. His work has been published in The New Yorker, Ploughshares, and Houghton Mifflin's Best American Short Stories.

M EDIA

Amerikanski Srbobran (The American Serb Defender). Published by the Serb National Foundation since 1906, this is the oldest Serbian bilingual weekly newspaper in the United States, and it has the largest circulation. It covers cultural, political and sporting events of interest to Serbian Americans.

O RGANIZATIONS AND A SSOCIATIONS

American Bosnian Association, Salt Lake City.

Address: 1102 West 400 North, Salt Lake City, Utah 84116.

Telephone: (801) 359-3378.

Bosnian-American Cultural Association .

Works to preserve Bosnian culture and teach Americans about Bosnia.

Contact: Dr. Hasim Kosovic.

Address: 1810 North Pfingsten Road, Northbrook, Illinois 60062.

Telephone: (312) 334-2323.

Bosnian-American Islamic Center.

Contact: Ramiz Aljovic.

Address: 3101 Roosevelt, Hamtramck, Michigan 48212-3745.

Community of Bosnia Foundation.

Works for a culturally pluralistic, multireligious Bosnia. Formed by volunteers in Haverford, Pennsylvania, in late 1993 to bring students to the United States.

Address: c/o Department of Religion, Haverford College, 370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, Pennsylvania 19041-1392.

Telephone: (610) 896-1027.

Friends of Bosnia.

Grassroots organization supporting a long-term and just peace. Organizes speaker series, interviews, conferences, rallies and humanitarian aid drives. Originally focused on serving western Massachusetts; now provides resources to organizations and individuals all across the United States.

Address: 85 Worcester Street, Suite 1, Boston, Massachusetts 02118.

Telephone: (617) 424-6906.

Fax: (617) 424-6752.

E-mail: FOB@CROCKER.COM.

Online: http://www.crocker.com/~fob/ .

Jerrahi Order of America.

Bosnian cultural, educational, and social relief organization made up of Muslims from diverse backgrounds. The Jerrahi Order has branches in New York, California, Indiana, Seattle, and Bosnia. Works to obtain scholarships for Muslim students.

Address: 884 Chestnut Ridge Road, Chestnut Ridge, New York 10977.

Telephone: (914) 356-0588.

E-mail: forbsp@igc.apc.org.

New England Bosnian Relief Committee.

Nonprofit provides donations to Bosnians and support and assistance to Boston-area Bosnian refugees.

Address: 54 Ellery Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02127.

Telephone: (617) 269-5555.

E-mail: nebrc@tiac.net.

Women for Women.

Raises money and offers support for Bosnian women.

Address: Suite 611, 1725 K Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20006.

S OURCES FOR A DDITIONAL S TUDY

Clark, Arthur L. Bosnia: What Every American Should Know. New York; Berkley Books, 1996.

Kisslinger, Jerome. The Serbian Americans. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1990.

Malcolm, Noel. Bosnia: A Short History. New York: New York University Press, 1996.

Shapiro, E. The Croatian Americans. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1989.

Silber, Laura, and Allan Little. Yugoslavia: Death of a Nation. New York: Penguin, 1995 and 1996.

Tekavec, Valerie. Teenage Refugees from Bosnia-Herzegovina Speak Out. New York: Rosen Publishing Group, 1995.

Source : http://www.everyculture.com/multi/A-Br/Bosnian-Americans.html